Tuesday morning, the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission unanimously moved to designate Dorrance Brooks Square a historic district. As Harlem continues to undergo a rapid transformation, often with individual historic sites targeted for redevelopment, the designation is a major win for preservationists and social justice activists. The newly approved historic district will serve as a reminder of the area's rich past, speaking to both the evolution of the neighborhood, as well as the African American community's contribution to NYC and the United States.

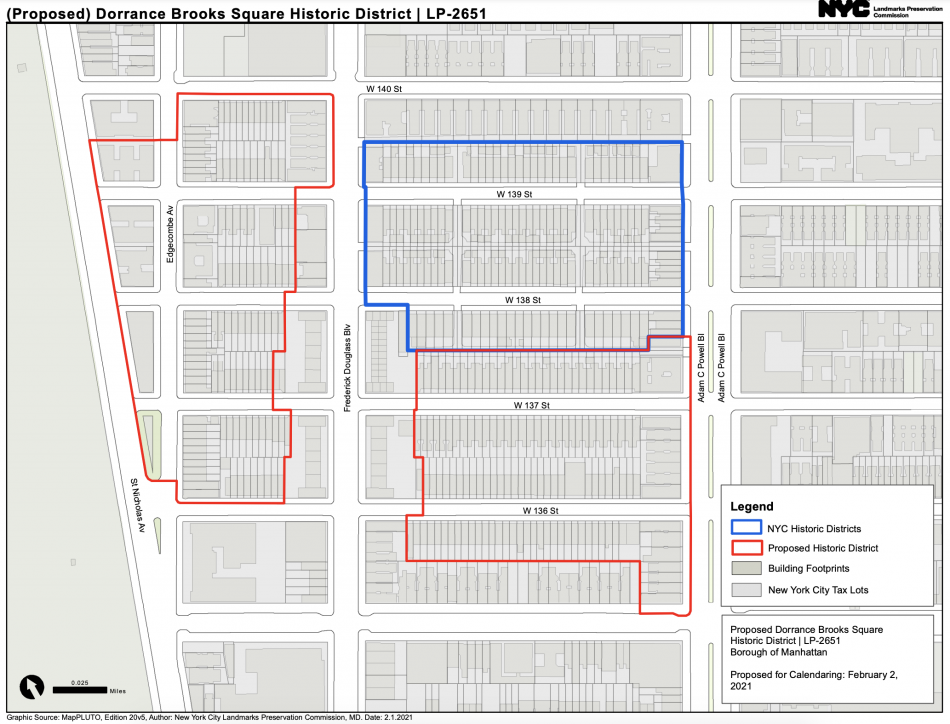

The area covered by the new historic district | Landmarks Preservation Commission

The area covered by the new historic district | Landmarks Preservation Commission

The proposed district consists of intact streetscapes of 19th and early 20th-century row houses, multi-family dwellings, and institutions, designed by prominent New York City architects within two sections on either side of Frederick Douglass Boulevard between West 136th Street and West 140th Street. Rowhouses, designed predominantly in the Renaissance Revival, Queen Anne, and Romanesque Revival styles, dominate the streets within the proposed historic district, while mixed-use and multi-family buildings are more common on the avenues.

The historic district is named after a local park dedicated in 1925 in honor of African-American infantryman Dorrance Brooks, who served with a segregated military regiment in the First World War and died in action. The area covered represents the area’s significant association with notable African-Americans in the fields of politics, literature, medicine, and education during the Harlem Renaissance from the early 1920s to the 1940s.

Over the years, the square has been a rallying point for civil rights protests starting in the 1920s. It is also closely associated with the Harlem Renaissance, and some of its past residents include W.E.B. DuBois, sculptor Augusta Savage, and actress Ethel Waters.

The area also includes two small hospitals, the Vincent Sanitarium and Hospital and the Edgecombe Sanitarium, which were founded by African American doctors to serve the local community when discriminatory barriers denied African American doctors the same privileges as their white counterparts.

- Harlem (Urbanize NYC)