From the editor: “L.A. Urbanized” is a series of articles exploring why Los Angeles is currently in the midst of an urban revolution and what it means for the city’s future. It documents the evolving development landscape of the region over the past few decades, identifies what key events brought about its urbanist turn, and considers what the impact of this transformation will be. Urbanize LA will publish one chapter of the 9-part series each Monday from April 2 through May 28.

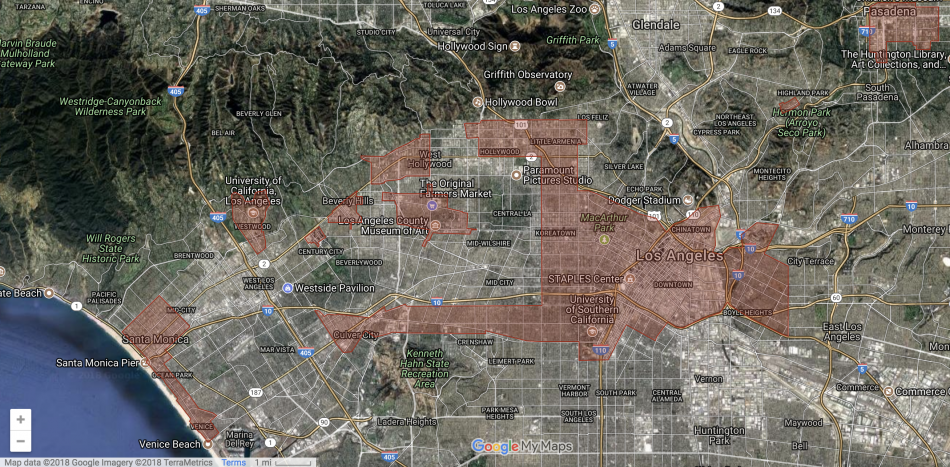

The Los Angeles of the popular imagination is a city of a vast sprawling scale, of freeways and boulevards, and of single family homes on quiet residential streets. These notions do indeed describe much of the Greater Los Angeles region, a sweeping territory encompassing hundreds of municipalities and neighborhoods across five counties, which roughly 18.5 million people call home. But any astute observer of this city must realize that appearances are not always the same as reality. While that is the stereotypical impression of LA, much of the city looks very little like that picture. And over coming decades, the prevailing imagery of the city might include towers in addition to houses, subways in addition to freeways, and jacarandas in addition to palms. Los Angeles is transforming before our very eyes.

After decades of seemingly limitless outward expansion, the city has ‘filled up’ at its sprawling low-density level, and the next LA is increasingly centered around a growing urban core that is set to redefine the region as we know it. There is a growing sense both in and out of LA that this place is entering a fundamentally new phase of its history. Christopher Hawthorne, the architecture critic for the Los Angeles Times, recently brought on as Chief Design Officer for Mayor Eric Garcetti, has been one of the more prominent voices promoting the notion of a “Third Los Angeles”. Recent conferences held Downtown have touched on similar topics. And out-of-town publications from GQ to the New York Times have written influential pieces chronicling the evolution of LA restaurants, bars, and more general lifestyle through the lens of the city’s increasing urbanization.

Urbanize LA has been the go-to source for information on what is changing in LA’s built environment. This series of articles will attempt to address the why and the so what related to the city’s transformation. It will describe what brought about the previous iterations of Los Angeles, evaluate why the city is changing in a fundamental fashion, and explore what the impact of this transformation will be.

* * *

Beginning its life as a little Spanish pueblo in the late eighteenth century, for its first 100 years Los Angeles was little more than a small town with a rough and tumble reputation. Though the City of LA seal proclaims “FOUNDED 1781”, our story is going to begin about 100 years later, when LA began to grow a fair bit more than the typical little pueblo. From this point, the scale, vigor, and inventiveness with which LA operated as a boom town was unusual. Aside from the temperate weather, the natural endowment of LA’s land was relatively poor, with few natural resources, insufficient water, and no good natural harbor. Los Angeles was forced into city-hood seemingly by the sheer willpower of its early leaders, whose zealous schemes to get LA off the ground have filled the pages of many historical books. A few generations later, the city fathers literally moved rivers and mountains to re-imagine LA as a sprawling behemoth, largely forsaking its traditional center in the process.

Moving forward to the modern day, developing a robust urban core in the city most known for suburbia can be seen as a similarly herculean endeavor. But DTLA was not built in a day. Structural forces have been evolving for several decades that made growth in Los Angeles much more likely to concentrate in its urban core, demographic and cultural developments have expanded demand for this sort of development and lifestyle, and a combination of public efforts and private initiatives have made these changes possible from the supply side.

This series adopts the framework of three main urban forms over LA’s history. There is LA 1.0, a more traditional monocentric city, stretching from the 1890s to 1945. There is LA 2.0, the sprawling suburbia many associate with LA today, from the end of WWII in 1945 into the 1990s. And there is LA 3.0, in certain respects a hybridization of the two previous forms, which has been developing since the 1990s. This series addresses the transition from LA 2.0 to LA 3.0, assessing why it is happening, what it means for the city moving forward, and what lessons other cities can learn from these stories told about Los Angeles specifically.

Los Angeles 1.0

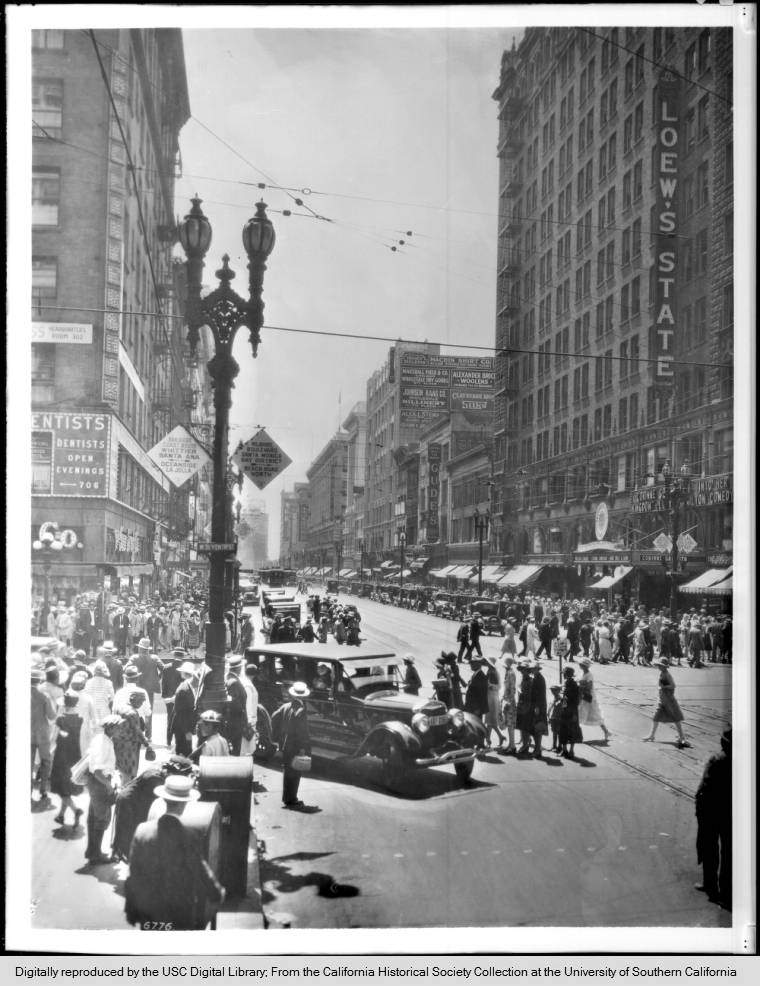

Early twentieth century Los Angeles was the sort of place that today’s dedicated urbanists might feel quite at home in: a more traditional, monocentric sort of city where most of the region’s economic and cultural life took place within a single, rail-fed urban core. In this early LA, the area of land now known as “Downtown Los Angeles” was known simply as “Los Angeles”, a city unto itself, separated by farmland from other clearly distinct Southern Californian cities such as Pasadena and Santa Monica. This ‘traditional’ Los Angeles, “LA 1.0”, lasted from the city’s true inception around the turn of the twentieth century up through the end of the Second World War.

LA 1.0 had its suburbs, to be sure, but these were mostly based on the streetcar system. This meant that they needed to be relatively dense and close to the urban core, given the cost and operation constraints of rail transit. It took a major technological transformation, the mass adoption of the automobile, to open the vast region to the sort of sprawling suburban development with which it has come to be associated.

Los Angeles 2.0

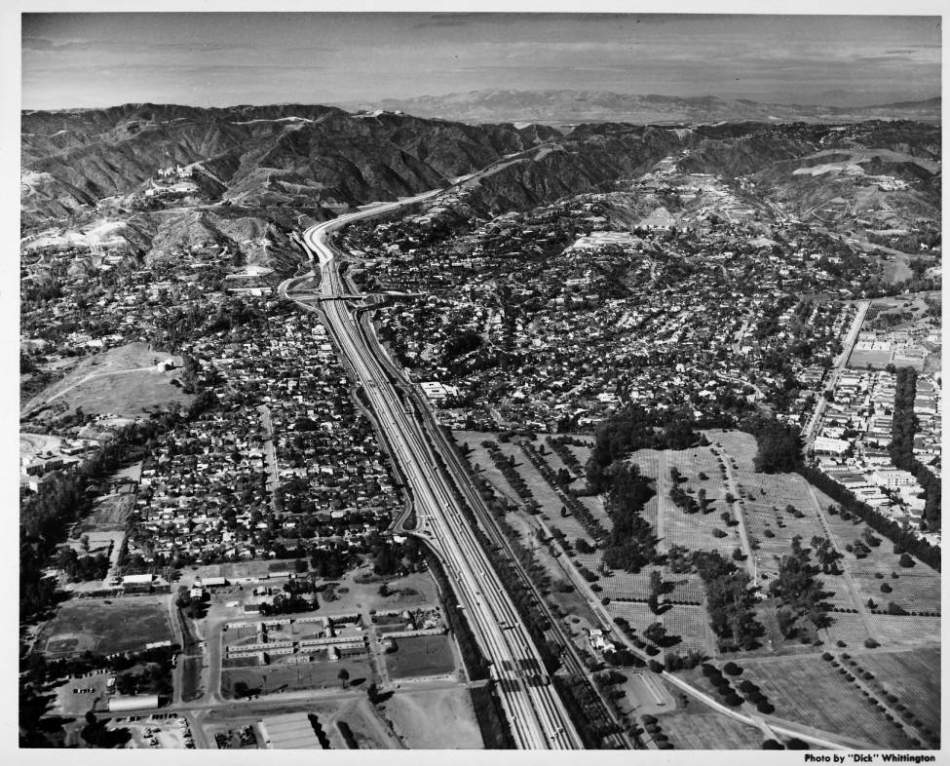

Over the decades ensuing after WWII, the character of Los Angeles was fundamentally transformed, to such an extent that the emergent “LA 2.0” can be considered an almost entirely new city unto itself. The key force behind the change was the advent of mass automobile ownership, which enabled Los Angeles, as well as most other cities around the world, to reshape itself in a dramatic new fashion. Mass transit by rail requires some degree of population density, in that rail commuters generally need to live and work within walking distance of railway stations. Being as railroads are expensive to build and trains expensive to operate, a low density population sprawl where a great many people can live in detached homes with private green space was simply economically unfeasible.

But automobile ownership fundamentally changed the name of the game, because roadways are relatively cheap to build and cars are relatively cheap to operate. Thus, this form of transit technology allowed for more distant lands to be colonized as suburbs. This model of settlement proved quite appealing for people during an age when urban cores were associated with grime, disease, pollution, crime, and immoral ways. Indeed, many saw it as a ‘best of both worlds’ between the city and the countryside, wherein suburban residents could have their own quiet and peaceful space, while maintaining easy access to the work and entertainment opportunities of a city using their cars on uncongested roads.

LA 2.0 was built on this model. Great wide boulevards and freeways made accessible land across the region which was previously too remote to be effectively connected to any population center. Mid-century Los Angeles offered Americans (and prospective immigrants) the opportunity for this sort of idyllic life — access to economic opportunity without needing to suffer the chaos and crowding many associated with urban life of the day. Accordingly, the Greater LA region’s population exploded during this period of time, tripling from 1940 to 1970 from 3.3 million to 10 million, twice the national population growth rate during for that time span.

Quickly finding itself as one of the largest metropolises in the world, Los Angeles simply could not accommodate all of these new arrivals within its historic urban core and its immediate hinterland, especially not given the low density lifestyle its new arrivals were seeking. So Los Angeles sprawled in every which direction, generally unconstrained by the sorts of barriers to horizontal growth — water, mountains, political boundaries — that other cities often experience. Promotional literature about LA County up through the 1940s touted its status as a hub for the dairy industry. But imagining bucolic farms in the region today is almost laughable, because over the course of the century the city swallowed all of this farmland and all of the lesser municipalities, subsuming them all into a new “Greater Los Angeles” megalopolis.

This new creation, LA 2.0, can almost be thought of as a fundamentally different city from LA 1.0. Both LA 1.0 and 2.0 featured “Hollywood” as the center of America’s entertainment industry, but the similarities are few and far between otherwise. While the other major LA 1.0 industry was oil, by the 1940s many of the oil wells in the region had dried up, and aerospace was developing as the new growth industry for the city. Geospatially, LA 1.0 was relatively cut off from the rest of the world — located beyond a great desert at the edge of the continent without a good natural port in an era before mass air travel. But by the coming of LA 2.0, LA had built the largest port in America, and the ushering in of the jet age and the interstate highway system connected LA to the outside world to a degree it had not been before. But more visibly, the urban form of the region was fundamentally re-created during this period.

The urban core of the Greater LA region, which more or less was Los Angeles during the 1.0 phase, practically evaporated from the cultural and economic life of most Angelenos during the 2.0 phase. Almost all of the commuter rail lines in the region were ripped out within two decades of the end of WWII. Business boomed in Southern California throughout the 2.0 period, but only a small portion of that growth was felt in DTLA. Rather, a number of smaller, ‘better’ downtowns were created within the numerous ‘urban villages’ across the region, such as Century City or Irvine. Almost all of the people who used to live in Downtown decamped for (or were pushed out to) the suburbs, leaving DTLA as a business center by day but a virtual ghost town by night. Viewed under this context, LA 2.0 appears in many respects not as the next natural phase of LA 1.0, but as an entirely new city that happened to be built around the same area. The degree to which the legacy of LA 1.0 remained relevant is a question with a profound impact on the future of Los Angeles, and one which will be explored further over the course of this series.

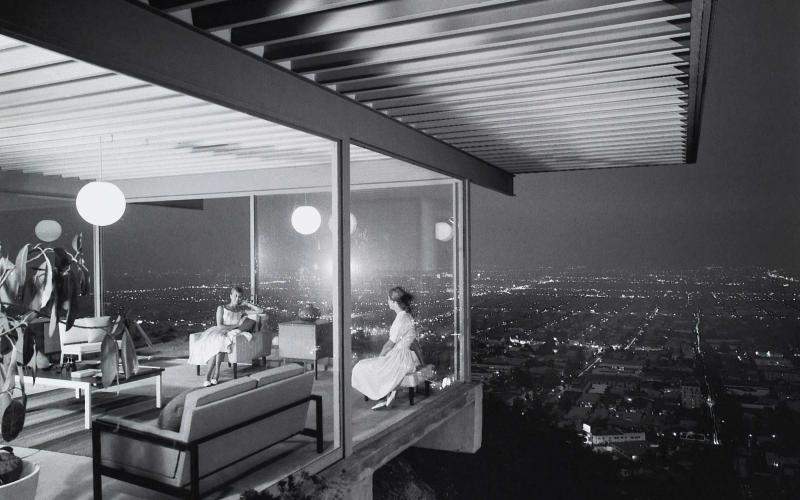

Perhaps the most authoritative book about LA 2.0 is Reyner Banham’s 1971 piece, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies. In this work, Banham explains Los Angeles through the lens of four separate ‘ecologies’. As the title suggests, each ecology is visually and culturally distinctive, with its own value sets, world views, and sensory experiences. Banham labels these four ecologies as “Surfurbia”, the various beach communities that hug the coastline of the region; the “Foothills”, which are the residential home for the city’s elites; (disparagingly) the “Plains of Id”, which are the utilitarian flatlands of the region where most people actually live and work; and “Autopia”, the freeway network and accessory uses, an ecology unto itself, which many Angelenos spend significant time navigating on a daily basis.

Conspicuously missing from this list of ecologies is any sort of urban core, or urban area generally, where life is lived as a pedestrian on the street or where movement is done by public transit. Banham does include a “Note on Downtown” in his book, but explicitly states that he intends to leave no more than just a note on it, declaring the old Downtown little more than a series of “unintegrated fragments” of cultural value from a bygone era, generally irrelevant to the lives of most people in LA during the time of his writing.

Post-War Urban Development

LA 2.0, viewed as its own, novel city, is a rather unusual one in terms of the timing when it came into being. Most globally important cities today were major cities even before WWII, the end of which coincided with the advent of mass automobile ownership in America. But this was not fully the case for Los Angeles. It was only in the years after WWII that Los Angeles truly boomed as a major global city, and it built itself during this boom phase with the expectation of near-universal adoption of the car. This expectation defined the urban form of LA 2.0.

Not very many major global cities ‘came of age’, so to speak, during the latter twentieth century, but those that did were generally built in a sprawled fashion — provided that they did not have physical constraints against growth. Few cities in the world today are so geared toward the car as certain major “Sun Belt” cities in America, such as Phoenix, Dallas, or Houston, all of which also experienced their explosive growth phases after mass car ownership became the expectation. Some cities that experienced transformative growth during this period did so in a dense fashion, but those cities are the clear exception. Examples of this sort of exception, such as Singapore, typically face very tight geographic constraints making sprawl unfeasible. Cities created from scratch during the late twentieth century, such as Dubai, Islamabad, or Brasilia, are almost exclusively spread-out and built for the automobile. In almost every case, even previously established, dense cities sprawled a fair bit toward the auto-focused suburbs during the latter twentieth century. Reading from this evidence, we can infer that once mass car ownership was available, car-focused sprawl was to some extent an economically efficient response to growth, at least in the short run. And this form of growth was generally supported in planning and government circles for several decades.

But these sorts of more recent urban creations are the exceptions amongst major global cities, in that most big cities today were already big cities before mass transit by car was ever an option. They had already built up substantial dense urban cores that were home to powerful stores of economic and cultural capital. These older cities suburbanized to some extent after WWII, but the suburbs could never completely replace their older urban cores and thus fundamentally transform their regional nature. For Los Angeles, the old urban core was not weighty enough to resist being swept away by the tidal wave of suburbanization and economic transformation; while the urban cores of many older cities had previously developed the heft to maintain their central position.

Los Angeles 3.0

As we sit here today, more than a half-century after the advent of LA 2.0, the winds of change are blowing stronger than the Santa Anas. The region is re-orienting itself, with an increasing focus paid to the urban core. After decades of abandonment and failed efforts at revitalization, Downtown Los Angeles is currently experiencing its largest development boom since the 1920s, and its population has nearly quadrupled over the past 15 years. Several other neighborhoods located within reasonably close proximity to DTLA are undergoing development booms of their own, in a dense, transit-oriented, and pedestrian-focused style, such that this central part of the Greater LA region is increasingly looking like a traditional urban core. At the same time, Los Angeles is in the process of building a comprehensive new public transit rail network centered on Downtown, and it is encouraging dense development to crop up within the vicinity of its emerging rail stations through City Planning programs such as Transit-Oriented Communities. A host of new cultural institutions are locating themselves within the region’s urban core. We may be in the midst of witnessing the movement from an LA 2.0 to an LA 3.0.

What does LA 3.0 look like, and what makes it clearly distinct from its predecessor? To be sure, there is little chance that any LA 3.0 will so totally subsume the existing LA 2.0 as did 2.0 to 1.0. The extent of the built environment under the 2.0 model today is simply too great to be completely transformed any time soon — barring exceptional growth, tragedy, or technological change. LA 3.0 is a hybridized model, not a return to the monocentric model of old but rather a re-introduction of an urban core to a city that functionally never had one in its existing form. In this model, Downtown LA and its surroundings are home to a plurality of the region’s cultural and economic power, if not a total predominance as might be the case in more traditional cities — the suburbs and secondary economic hubs will continue to play an important role in LA life. But in a city with many ‘urban villages’, Downtown seemingly functions as the ‘neutral ground’ between them all, where the various communities of the region can co-inhabit the same space.

To play on Banham’s analysis of the ‘four ecologies’, the key difference between LAs 3.0 and 2.0 is the addition of a “Fifth Ecology”, the rail-based urban core, not eliminating the previous four ecologies, but adding a new dimension to this metropolitan context. To be clear: the scope of this ecology is not limited to Downtown LA specifically, but extends more broadly to the parts of the city that are built in a dense, transit-oriented fashion, and have recently found themselves defined in large part by their rail connection to Downtown Los Angeles. Thus, this ecology would include neighborhoods such as Koreatown, East Hollywood, Boyle Heights, Culver City, and more, in addition to Downtown proper. Most of these neighborhoods would likely be part of the “Plains of Id” according to Banham’s definitions, but their natures today have clearly changed from how they were in the 1970s.

LA is in a rare position to pursue this sort of hybridized model, in that its pre-war urban core was big enough that it carries some weight, but small enough that its grip was never so firm as to continue dominating the region following from the introduction of the automobile. The suburbs could never truly vacate the core power of a place like Manhattan, because there was simply too much economic and cultural capital locked up on that island. Conversely, cities like Phoenix or Houston had far less developed urban cores by the advent of mass automobile ownership, and thus today there would be relatively little basis on which to anchor a return to urban densification. LA is somewhat unique in this respect in that it strikes a middle ground between these two extremes. It has the legacy of an old urban center, even though Downtown was largely vacated for decades, but which already has the solid physical and cultural bones – the government offices, the dusty old theaters and commercial buildings, the legacy businesses and social clubs – to function as the main center for the region once it was reactivated. As such, the study of the ‘re-urbanization’ of LA is unlike that of the urban renaissances of other great American cities whose urban cores never truly ceased their roles at the center of metropolitan life; but it is also unlike the study of projects to invent an urban core from scratch as has been attempted in several cities around the world.

The Causes and Effects of Los Angeles 3.0

What is responsible for bringing about LA 3.0? Answering this question will be the primary purpose of this series. In certain respects, the story of the move toward suburbanization after WWII and the revival of the urban core in recent years is a familiar one in America, as this process has taken place in many cities across the country. Indeed, many of the key causes of the process for other cities are similar to causes for Los Angeles. But the case for Los Angeles is unique, I will argue, because the city’s growth periods were concentrated during the automobile and suburban era to a much greater extent than most other American cities, and also because the movement toward re-urbanization in Los Angeles was more engineered and less a response to market forces than is the case in other such stories. Structurally, I will approach the question of what brought about this revolution of affairs by evaluating the evolving background context leading up the beginning of the transformation, by identifying the key events that set this transformation in motion, and by exploring the factors that have seemingly sent this transformation into overdrive over the past five years. Ultimately, I will explore what the impact of this transformation will be on Los Angeles and its people, and what lessons cities across the world can draw from this story.

In short, LA 3.0 had to evolve out of LA 2.0 because the advantages of the 2.0 model could not take the strain of its own successes. The mass population the low density model attracted eliminated the benefits of this system through congestion and unaffordable housing. With ever-increasing population in the LA area, easy commutes have given way to legendary traffic jams, and inexpensive single family homes have given way to the least affordable housing market in the country. Congestion on the roads effectively gave LA the physical constraint to growth it never had before. It was as if the urban core of the region had become an island, because access to it from outside took a prohibitively long period of time due to traffic. Essentially, the region finally ‘filled up’ at the low density level it was built at through the 2.0 model, and thus new population growth needed to be accommodated by denser development patterns.

These background patterns were expressed through economic, political, and cultural trends over the past few decades that set the stage for the DTLA revival and the growth in urban concentration more generally. There were a series of late 1990s ‘catalysts’ that set this process generally (and the DTLA renaissance specifically) in motion. The pattern of increasing urban development was put on hold for a few years by the Great Recession of the late ‘00s. But by 2012, institutional and foreign capital began injecting itself into Downtown and urban LA development, accelerating this process of re-urbanization beyond the expectations of its most enthusiastic supporters. Considering the outlook for the region over the coming few decades, where the population is expected to grow from 18.5 million to 25-30 million by 2050 – but where, unlike in the past, physical constraints to outward growth have been reached – the future of LA increasingly looks up and down: to the tower and the subway.

But what will this sort of future mean to the people who live in LA? The transition from LA 1.0 to 2.0 was certainly quite disruptive, making life worse for many Angelenos even while it opened the possibility for the city to expand and provide for opportunities that had never existed before. We should expect that the transition from 2.0 to 3.0 is likely to have impacts of a similar scale. From an economic perspective, I will argue that the movement to LA 3.0 is likely to help the region, in that certain pitfalls of the broken 2.0 model have been holding the local economy back. From a social and cultural perspective, the outcomes will likely be more muddled. In certain respects, it appears that under the 3.0 model the various communities of LA will become more closely linked as they are made accessible to one another by denser living and public transit, and as a result Angelenos will develop a stronger sense of civic identity. At the same time, this new-found interconnectedness will likely result in the disruption of certain existing neighborhoods and communities by making the land on which they live suddenly valuable beyond what they are able to pay. Navigating these competing challenges and opportunities will be LA’s greatest task as it proceeds into its third iteration.

Jason Lopata works as a land use consultant with Craig Lawson & Co., LLC, helping real estate development projects in LA navigate the city approvals process. Jason previously spent time on the Business Team of LA Mayor Eric Garcetti. He also writes articles on globalization and urban development for Stratfor, the geopolitical analysis website. Jason received his bachelor’s degree from Stanford University and completed programs of study at the University of Oxford and at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management. While at Stanford, he founded and led the student real estate organization, and authored his senior thesis on Los Angeles development over the past 30 years.